There isn’t only one correct way to perform any exercise. There’s a safe zone or a range of techniques you can use but based on who you ask, you’ll likely get a different answer on what the right way is to do a triceps curl or a pushup or a squat.

It’s okay to have a difference of opinion, but it becomes a problem when it endangers someone’s health.

I was inspired to write this article after an interaction with a patient the other day. She came in with acute low back pain. Even though there were some underlying issues, we were able to narrow down a few aggravating factors. And to my surprise, the main culprit was squatting – primarily squatting while significantly restricting knee movement.

We spent the entire session going over why it was okay for her to allow her knees to go past the toes while squatting especially if she was increasing the depth of her squats.

This technique cue has been taken out of context and many have forgotten why this was advised in the first place.

In this article, we’ll dig deep into what the literature says about knees going past the toes in a squat or lunge and share some key takeaways.

Keep reading if you’ve ever been in a similar place as my patient – confused about what the right squatting technique is and why there are such contrasting views out there.

First, Where Did This Spatting Technique Come From?

No one really knows where the myth around knees and toes started from. But my best guess is that it was given as an instruction to prevent a specific type of pain or injury and just snowballed from there.

Some people cite a 2003 study by Fry et al. as their source for not allowing the knees to go beyond the toes. Their reasoning is that more anterior motion of the knees puts additional pressure on the joint.

The study showed that the more forward your knees go, the more torque there is around them (150.1 with unrestricted knees and 117.3 with the restricted knee movement).

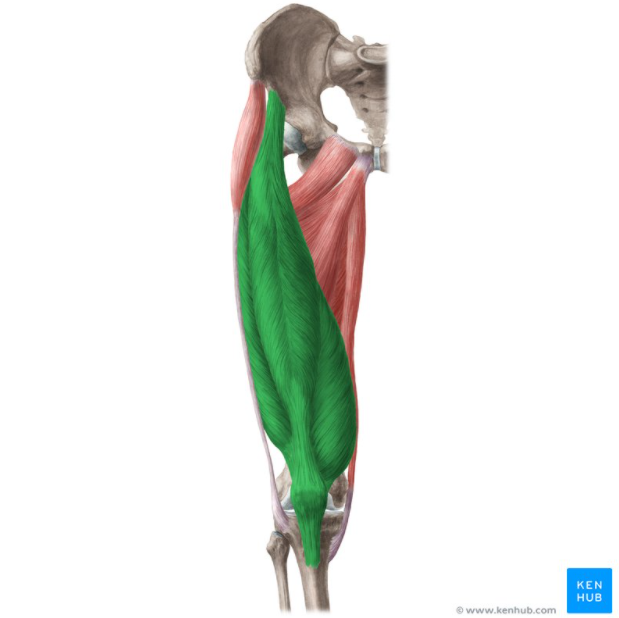

Our quadriceps muscles attach at the knees (patella) and the ‘torque’ is the force they apply to control the knee joint motion while squatting. Quads apply force in both directions – while going into the squat and while standing up straight again.

You can see the Quadriceps in green. Image source: Kenhub

So the study did conclude that the squat or lunge posture in which the knees didn’t go past the toes puts less tension on the knees, but they also concluded that it puts an excessively large torque on the hips and low back (28.2 with unrestricted knees and 302.7 with restricted knee motion).

Is It Safe For Knees to Go Past Your Toes?

The short answer is yes!

It’s safe for your knees to go past the toes anteriorly in a squat or a lunge as long as you follow the correct biomechanical sequence and recruit the right muscles – contract the glutes first to move the hips then engage the knees.

The key is to not let your knees wobble from side to side because that puts the knee ligaments under increased stress. That can be dangerous for an untrained knee and cause instability.

Here’s the science to support the above statements:

Your knees can handle the increased load

Your knees going past the toes do put additional pressure on your patellar tendon. But here’s the thing –this load is well within the range of what your knees can handle.

A study by Rafael F. Escamilla concluded that parallel squats were not injurious to healthy knees. He also found that squats when performed properly didn’t compromise knee joint stability at all. In fact, squat training can enhance stability by improving lower limb muscles’ strength.

Another study found that functional adaptation of our body structures plays a major role in decreasing the risk of injury. Knees moving past the toes are not as big a risk for someone who’s had proper training as compared to a weekend warrior.[i]

If you start training with lower loads (preferably just bodyweight initially) and work your way into a deeper squat, then your knees should be able to handle the increased load that squat posture puts on them.

Proper form saves your hips from taking all the load

The 2003 research from the University of Memphis showed a 28% increase in knee load while squatting with knees past the toes. Restricting this natural knee motion puts the hips under 1070% more load. The math here is obvious.[ii]

If you want to distribute the weight evenly between the low back, hip and knees, then you must allow the knees to move past the toes anteriorly.

Another study found that partial squat exercises put 6 to 10 times the bodyweight on the low back (L3 and L4 segments of the lumbar spine). The amount of load was influenced by the trunk flexion which can be more when you restrict your knee’s forward motion.

Knees going past the toes helps you keep your balance in a squat

Have you ever seen a baby squat? Or looked at one of those old-timey photos where people cooked while squatting down? Or watched an Olympic weightlifter squat?

If you have, you must have seen that their knees go well past the toes. That’s because you have to do that to maintain your balance. The deeper you’re squatting, the more forward knee motion you’ll need.

The important thing is for your center of mass to remain over the middle of the foot.

The important thing is for your center of mass to remain over the middle of the foot. That will require a different range of knee movement depending on the depth of your squat. [iii]

When Should Knees Not Go Past the Toes?

Usually, we recommend our rehab patients keep the knees behind the toes. That’s because excessive forward motion of the knees puts undue load on the patellar tendon and the patella-femoral joint.

One thing to remember here is that this ‘excessive forward motion’ is subjective and varies from patient to patient. People with longer limbs have more apparent knee movement than their counterparts, and we don’t have any authentic scientific research that can tell us what excessive is in this context.

So it’s best to err on the side of caution when you have anterior knee pain[iv] or recovering from knee surgery.

Generally, the recommendation from the literature is to stay between 0° to 50° of knee flexion during recovery. This position puts the least amount of patellofemoral compressive forces and tibiofemoral compressive and shear forces on the knee.

Knees, Toes and Squats – Key Takeaways

Your knee moving over the toes in a deep squat is normal. Just make sure that you’re following the right technique and initiating movement at the hips before the knees to begin your squat and keep the spine neutral.

That’ll prevent any unnecessary forward motion and distribute the load evenly.

So your key takeaways are:

- It’s safe to take your knees past the toes anteriorly in a squat or a lunge.

- The key is to not let your knees wobble from side to side and keep them in line with the toes for maximum efficiency.

This misconception is just one of many that are commonly believed and practiced in the strength and conditioning world.

It can happen when scientific literature is misinterpreted by people who fail to understand the results or when fitness instructors give you generic advice without properly assessing your joints. That’s why you should always reach out to trained professionals to help clarify queries and to guide you about rehab or training. You can contact our Healing with PT team to get the help you need.

[i] https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s40279-013-0073-6

[ii] https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/14636100/

[iii] https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/22505136/

[iv] https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S1836955314000915